- Parents Home

- Para Padres

- A to Z Dictionary

- Allergy Center

- Asthma

- Cancer

- Diabetes

- Diseases & Conditions

- Doctors & Hospitals

- Emotions & Behavior

- First Aid & Safety

- Flu (Influenza)

- Food Allergies

- General Health

- Growth & Development

- Heart Health & Conditions

- Homework Help Center

- Infections

- Newborn Care

- Nutrition & Fitness

- Play & Learn

- Pregnancy Center

- Preventing Premature Birth

- Q&A

- School & Family Life

- Sports Medicine

- Teens Home

- Para Adolescentes

- Asthma

- Be Your Best Self

- Body & Skin Care

- Cancer

- Diabetes

- Diseases & Conditions

- Drugs & Alcohol

- Flu (Influenza)

- Homework Help

- Infections

- Managing Your Weight

- Medical Care 101

- Mental Health

- Nutrition & Fitness

- Q&A

- Safety & First Aid

- School, Jobs, & Friends

- Sexual Health

- Sports Medicine

- Stress & Coping

Chest Wall Disorder: Pectus Excavatum

What Is Pectus Excavatum?

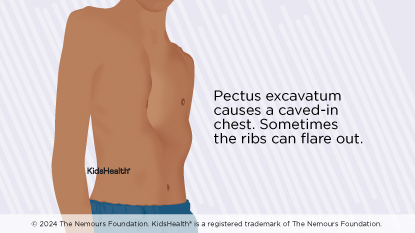

Pectus excavatum is when the ribs and sternum (breastbone) grow inward and form a dent in the chest. This gives it a concave or caved-in shape, which is why the condition is also called "funnel chest" or "sunken chest." It can be mild or severe. When it’s severe, there can be problems with the heart and lungs.

Some kids are born with the condition. Other times there’s no sign of it until puberty. It’s common for pectus excavatum (PEK-tus eks-kuh-VA-tum) to get worse during growth spurts.

What Causes Pectus Excavatum?

Doctors don't know exactly what causes pectus excavatum. In some cases, it runs in families. Males have it more often than females.

Kids who have it may also have another health condition, like:

- scoliosis

- Marfan syndrome

- Poland syndrome

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (when the tissue connecting body parts is weak)

Genetic tests can check for these and other related conditions in children with pectus excavatum.

What Are the Signs & Symptoms of Pectus Excavatum?

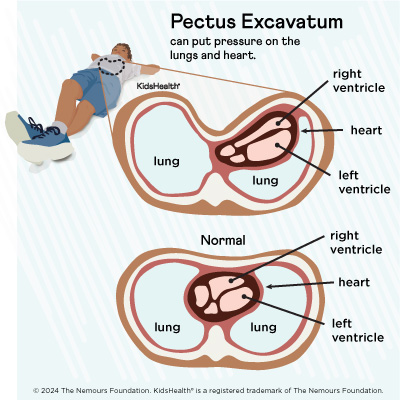

Mild pectus excavatum might be barely noticeable. But severe cases can cause a dent in the chest that may be deeper on one side. This can put pressure on the lungs and heart so they don’t have enough room to work as they should.

The ribs may stick out on one side of the chest. Other times the lower ribs jut out. This is called rib flare and can make younger children look like they have a potbelly. In newborns, infants, and toddlers, the chest may suck in when they breathe, laugh, or cry.

Older kids may have trouble exercising or keeping up with other kids their age. They also might get dizzy when standing up. Sometimes they have chest pain that comes and goes, tiredness, or shortness of breath. They may also have a rapid heartbeat or heart palpitations (irregular heartbeats).

Pectus excavatum tends to get worse when kids have growth spurts. When they've finished growing, the condition probably won't change.

How Is Pectus Excavatum Diagnosed?

Doctors diagnose pectus excavatum based on a physical exam. If needed, they might also order tests like:

- a CT scan and/or a chest MRI to see how much the heart and lungs are compressed or pushed down

- an echocardiogram to test how well the heart works

- lung function tests to check how well the lungs work

- exercise stress testing to see how much kids can exercise

How Is Pectus Excavatum Treated?

Kids with pectus excavatum will need treatment if they have symptoms or are bothered by how their chest looks. There are a few options to fix the shape of the chest.

Vacuum Bell Device

A device called a vacuum bell can be used at home. It’s placed on your child’s chest and is connected to a pump that sucks the air out of the device. This makes a vacuum that pulls the chest forward. Over time, the chest wall stays forward on its own.

Kids wear the vacuum bell each day for several hours. It can take 3–6 months to see any changes. The device tends to work better on younger children but can be used for all ages.

Surgery

If surgery is needed, doctors may do one of these procedures:

- The Nuss procedure or minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum (MIRPE). Minimally invasive means that only a few small incisions (cuts) are needed. The surgeon puts one or more curved metal bars in the chest to push out the breastbone and ribs. Sometimes a stabilizer bar is added to keep it all in place. The chest should be permanently reshaped in 2–3 years, and the surgeon will take out the bars. This is the most common surgery used to fix pectus excavatum.

- The Ravitch procedure or the open procedure. First, a surgeon removes that connects the ribs to the breastbone. Then, they place a support system in the chest to hold it in the right position. As new cartilage grows back, the chest and ribs stay flat. The support is taken out after about 6 months.

Physical Therapy

Doctors also might suggest physical therapy and exercises. These can make the chest muscles stronger and improve posture.

What Else Should I Know?

All kids with pectus excavatum should be seen by a chest wall surgeon. The condition can cause problems even when it doesn’t look very severe from the outside. Most kids and teens who have treatment do very well and are happy with the results.

© 1995- The Nemours Foundation. KidsHealth® is a registered trademark of The Nemours Foundation. All rights reserved.

Images sourced by The Nemours Foundation and Getty Images.