- Parents Home

- Para Padres

- A to Z Dictionary

- Allergy Center

- Asthma

- Cancer

- Diabetes

- Diseases & Conditions

- Doctors & Hospitals

- Emotions & Behavior

- First Aid & Safety

- Flu (Influenza)

- Food Allergies

- General Health

- Growth & Development

- Heart Health & Conditions

- Homework Help Center

- Infections

- Newborn Care

- Nutrition & Fitness

- Play & Learn

- Pregnancy Center

- Preventing Premature Birth

- Q&A

- School & Family Life

- Sports Medicine

- Teens Home

- Para Adolescentes

- Asthma

- Be Your Best Self

- Body & Skin Care

- Cancer

- Diabetes

- Diseases & Conditions

- Drugs & Alcohol

- Flu (Influenza)

- Homework Help

- Infections

- Managing Your Weight

- Medical Care 101

- Mental Health

- Nutrition & Fitness

- Q&A

- Safety & First Aid

- School, Jobs, & Friends

- Sexual Health

- Sports Medicine

- Stress & Coping

Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)

What Is a Ventricular Septal Defect?

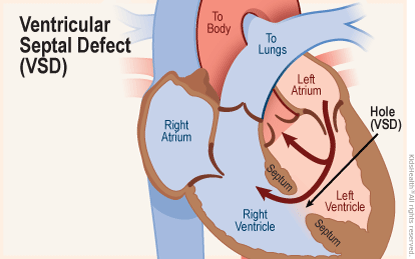

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) — sometimes referred to as a hole in the heart — is a type of congenital heart defect. In a VSD, there is an abnormal opening in the wall between the main pumping chambers of the heart (the ventricles).

VSDs are the most common congenital heart defect. Most VSDs are diagnosed and treated successfully with few or no complications.

30-Second Summary: Ventricular Septal Defect

Learn the basics in 30 seconds.

What Happens in a Ventricular Septal Defect?

The right ventricle and left ventricle of the heart are separated by shared wall, called the ventricular septum. Kids with a VSD have an opening in this wall. As a result:

- When the heart beats, some of the blood in the left ventricle (which has been enriched by oxygen from the lungs) flows through the hole in the septum into the right ventricle.

- In the right ventricle, this oxygen-rich blood mixes with the oxygen-poor blood and goes back to the lungs.

The blood flowing through the hole creates an extra noise, which is known as a heart murmur. Doctors can hear the heart murmur when they listen to the heart with a stethoscope.

VSDs can be in different places on the septum and can vary in size.

What Causes a Ventricular Septal Defect?

Ventricular septal (ven-TRIK-yu-lar SEP-tul) defects happen as a baby's heart develops before birth. The heart develops from a large tube, dividing into sections that will eventually become the walls and chambers. If there's a problem during this process, a hole can form in the ventricular septum.

In some cases, the tendency to develop a VSD may be due to genetic syndromes that cause extra or missing pieces of chromosomes. Most VSDs, though, have no clear cause.

What Are the Signs & Symptoms of a Ventricular Septal Defect?

Whether a VSD causes any symptoms depends on the size of the hole and its location. Small VSDs usually won't cause symptoms, and might close on their own.

Older kids or teens who have small VSDs that don't close usually have no symptoms other than the heart murmur. They might need to see a doctor regularly to make sure the VSD isn't causing any problems.

Medium and large VSDs may cause noticeable symptoms. Babies may have faster breathing and get tired when they try to feed. They may start sweating or crying while feeding, and may gain weight slowly.

These signs generally indicate that the VSD will not close by itself, and the child may need heart surgery. Usually, this is done in the baby's first 3 months of life to prevent other problems. A cardiologist can prescribe medicine to lessen symptoms before the baby has surgery.

What Problems Can Happen?

Infants with a large VSD can develop heart failure, and have feeding problems that lead to poor weight gain. They also may get chest infections often. Children with a small VSD are at risk for developing endocarditis, an infection of the inner surface of the heart caused by bacteria in the bloodstream. Bacteria are always in our mouths, and small amounts get into the bloodstream when we chew and brush our teeth.

Good dental hygiene to reduce oral bacteria is the best way to protect the heart from endocarditis. Kids should brush and floss daily, and see their dentist regularly. In general, patients with simple VSDs don't need to take antibiotics before dental visits, except for the first 6 months after VSD surgery.

How Are Ventricular Septal Defects Diagnosed?

Doctors usually find a VSD in a baby's first few weeks of life during a routine checkup. They'll hear the heart murmur, which has certain features that let them know it's not caused by something else.

If your child has a heart murmur, the doctor may refer you to a pediatric cardiologist (a doctor who diagnoses and treats childhood heart conditions).

The cardiologist will do an exam and take your child's medical history. If the doctor thinks there's a VSD, they may order tests such as:

- a chest X-ray: a picture of the heart and surrounding organs

- an electrocardiogram (EKG): a record of the heart's electrical activity

- an echocardiogram: an ultrasound of the heart. Often, this is the main way doctors diagnose a VSD.

- a cardiac catheterization: this provides information about the heart's structures and the blood pressure and blood oxygen levels in its chambers. This test usually is done for a VSD only when more information is needed than the other tests can give. (It's sometimes also used to close certain kinds of VSDs.)

How Are Ventricular Septal Defects Treated?

Treatment depends on a child's age and the size, location, and severity of the VSD. A child with a small defect that causes no symptoms may only need to visit a cardiologist regularly to make sure there are no other problems.

In many kids, a small defect will close on its own without surgery. Some might not close, but they won't get any larger. Kids with small VSDs usually don't need to restrict their activities.

Kids with medium to large VSDs might need prescription medicines to aid circulation and help the heart work better. Medicines alone, though, won't close the VSD. So, the cardiologist may recommend heart surgery to fix the hole. In rare cases, the VSD could be closed by cardiac catheterization instead.

Heart Surgery

Surgery usually is done within the first few weeks to months of a child's life. The surgeon makes an incision in the chest wall and a heart-lung machine will maintain circulation while the surgeon closes the hole. The surgeon can stitch the hole closed directly or, more commonly, will sew a patch of manmade surgical material over it. Eventually, the tissue of the heart heals over the patch or stitches. By 6 months after the surgery, tissue will completely cover the hole.

Cardiac Catheterization

Rarely, cardiologists may close some types of VSDs with cardiac catheterization. They insert a thin, flexible tube (a catheter) into a blood vessel in the child's leg that leads to the heart. They guide the tube into the heart to make measurements of blood flow, pressure, and oxygen levels in the heart chambers. A special implant, shaped into two disks formed of flexible wire mesh, is positioned into the hole in the septum. The device is designed to flatten against the septum on both sides to close and permanently seal the VSD.

What Else Should I Know?

In most cases, kids who have VSD surgery recover quickly and with no complications. But doctors will closely watch them for signs or symptoms of any problems. Your child will need follow-up visits with a cardiologist for a while.

If your child has trouble breathing, call your doctor or go to the emergency room right away. Other signs of a problem include:

- poor appetite or trouble feeding

- failure to gain weight or weight loss

- listlessness or decreased activity level

- a long-lasting or unexplained fever

- increasing pain, tenderness, or pus oozing from the surgery site

Call your doctor if you notice any of these signs in your child after surgery to close the VSD.

Having your child diagnosed with a heart condition can be scary. But the good news is that your pediatric cardiologist is very familiar with VSDs and how best to manage them. After surgery, most kids go on to live healthy, active lives.