- Home

- Parents Home

- Allergy Center

- Asthma Center

- Cancer Center

- Diabetes Center

- A to Z Dictionary

- Emotions & Behavior

- First Aid & Safety

- Food Allergy Center

- General Health

- Growth & Development

- Flu Center

- Heart Health

- Homework Help Center

- Infections

- Diseases & Conditions

- Nutrition & Fitness Center

- Play & Learn Center

- School & Family Life

- Pregnancy Center

- Newborn Center

- Q&A

- Recipes

- Sports Medicine Center

- Doctors & Hospitals

- Videos

- Para Padres

- Home

- Kids Home

- Asthma Center

- Cancer Center

- Movies & More

- Diabetes Center

- Getting Help

- Feelings

- Puberty & Growing Up

- Health Problems of Grown-Ups

- Health Problems

- Homework Center

- How the Body Works

- Illnesses & Injuries

- Nutrition & Fitness Center

- Recipes & Cooking

- Staying Healthy

- Stay Safe Center

- Relax & Unwind Center

- Q&A

- Heart Center

- Videos

- Staying Safe

- Kids' Medical Dictionary

- Para Niños

- Home

- Teens Home

- Asthma Center

- Be Your Best Self Center

- Cancer Center

- Diabetes Center

- Diseases & Conditions

- Drugs & Alcohol

- Expert Answers (Q&A)

- Flu Center

- Homework Help Center

- Infections

- Managing Your Medical Care

- Managing Your Weight

- Nutrition & Fitness Center

- Recipes

- Safety & First Aid

- School & Work

- Sexual Health

- Sports Center

- Stress & Coping Center

- Videos

- Your Body

- Your Mind

- Para Adolescentes

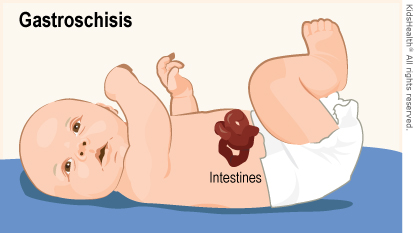

Gastroschisis

What Is Gastroschisis?

Gastroschisis is when a baby is born with the intestines sticking out through a hole in the belly wall near the belly button. Sometimes other organs also stick out. Gastroschisis (gast-roh-SKEE-sis) is a life-threatening condition that needs treatment right away.

30-Second Summary: Gastroschisis

Learn the basics in 30 seconds.

What Happens With Gastroschisis?

In normal prenatal development:

- As the organs inside an unborn baby's belly form, the intestines push out through a hole in the belly wall.

- Later, they twist and move back inside the belly, and the hole closes.

When a baby has gastroschisis:

- The intestines grow correctly at first, but stay outside of the belly, keeping the hole in the belly wall from closing.

- When the baby is born, the intestines are visible. Often, they're damaged from weeks of soaking in the amniotic fluid in the womb (uterus). The baby needs treatment right away.

What Are the Signs & Symptoms of Gastroschisis?

Babies born with gastroschisis have some of their intestines on the outside of their belly. They will lose heat and water very quickly from the intestines, causing:

- too much water loss (dehydration)

- a body temperature that gets too low (hypothermia)

Other organs may stick out along with the intestines, including the baby's:

What Causes Gastroschisis?

Doctors don't know why gastroschisis happens. It is probably due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

Gastroschisis is more likely when the mother:

- is under age 20

- smokes during her pregnancy

- drinks alcohol

Gastroschisis is more common now than it has been in the past, but doctors don't know why.

How Is Gastroschisis Diagnosed?

A pregnant woman doesn't have any symptoms during pregnancy when her baby has gastroschisis. But doctors might find gastroschisis before the baby is born when the mother has a:

- routine screening ultrasound scan (prenatal ultrasound)

- blood test for a protein called alpha-fetoprotein, which usually runs at a higher level than normal when a fetus has gastroschisis

If the mother did not have prenatal tests, the doctor will diagnose gastroschisis at birth because part of the intestine is outside the baby's body.

How Is Gastroschisis Treated?

Most babies with gastroschisis have a medical care team that includes:

- a high-risk pregnancy specialist (called a maternal-fetal medicine specialist or perinatologist)

- a neonatologist (a pediatrician specializing in complex newborn care)

- a pediatric surgeon

- delivery and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) critical care nurses

When a baby is diagnosed with gastroschisis, the parents and care team choose a location for the baby's birth that has an advanced NICU and decide whether vaginal delivery or cesarean section (C-section) is best for the mother and baby.

When the baby is born, a pediatric surgeon sees the baby to decide whether surgery is needed. The NICU care team will:

- Put the baby's lower half and the intestines in a special plastic bag to keep the intestines from losing too much water and to reduce heat loss. If needed, a special bag called a silo can be used. A silo can be slowly tightened to help the intestines shrink and go back into the belly.

- Keep the intestines as empty as possible so they can go back into the body. They do this by draining the stomach with a nasogastric (NG) feeding tube and feeding the baby only through an intravenous (IV) line.

What Happens After the Intestines Are Back in the Belly?

When the intestines are back in the belly (either naturally or with surgery), the baby will need to stay in the hospital for a month or more. At first, they may need help breathing if the intestines and other organs in the belly push up on the breathing muscle (diaphragm).

The baby will also need to slowly move from IV feedings to feedings by mouth. This takes time in all babies healing from gastroschisis. At first, only a small amount of pumped breast milk or formula will be given to the baby. Babies can get this through:

- an NG feeding tube

- a mouth-to-stomach (orogastric, OG) feeding tube

- a bottle

The amount of breast milk or formula will be slowly increased as the amount from the IV line is slowly decreased until the baby no longer needs the IV nutrition.

What Problems Can Happen?

While in the hospital, the care team watches for problems such as:

Atresia

Sometimes a baby with gastroschisis can have a blockage in the intestine called an atresia (eh-TREE-zhuh). It can be hard to see this when the baby is born due to the swelling of the intestine. It may not show up until after the intestines are back in the belly. If the intestines are back in the body and the baby can’t feed and is vomiting, doctors check for an atresia. If one is found, surgery is done to take it out.

Short Gut Syndrome

A baby whose healthy small intestine is much shorter than usual can have a rare condition called short gut syndrome (or short bowel syndrome). This means the baby can't absorb enough nutrition from digested food to grow and thrive. This can happen if:

- The gastroschisis abdominal wall defect partially closes and restricts blood flow to the intestine.

- The intestine twists and cuts off its own blood supply.

A baby with short gut syndrome needs extra nutritional support and other medical care.

What Else Should I Know?

Almost all babies born with gastroschisis survive if they receive prompt treatment.

The medical challenges of gastroschisis can be stressful for your child and you. But you're not alone. The care team will work together to help manage problems, and to support your family.

You also can find more information and support online at Avery's Angels.

© 1995- The Nemours Foundation. KidsHealth® is a registered trademark of The Nemours Foundation. All rights reserved.

Images sourced by The Nemours Foundation and Getty Images.