Apnea of Prematurity

What Is Apnea of Prematurity?

Apnea of prematurity (AOP) is when a premature (or preterm) baby:

- pauses breathing for more than 15 to 20 seconds

or - pauses breathing for less than 15 seconds, but has a slow heart rate or low oxygen level

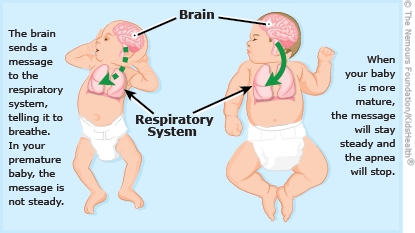

After they're born, babies must breathe continuously to get oxygen. In a premature baby, the part of the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) that controls breathing is not yet mature enough for nonstop breathing. This causes large bursts of breath followed by periods of shallow breathing or stopped breathing.

Apnea of prematurity usually ends on its own after a few weeks. Once it goes away, it usually doesn't come back. But it can be frightening while it's happening.

What Happens in Apnea of Prematurity?

Apnea of prematurity is fairly common in preemies. Doctors usually diagnose the condition before the mother and baby are discharged from the hospital, and the usually goes away on its own as the infant matures.

Generally, babies who are born at less than 35 weeks' gestation have periods when they stop breathing or their heart rates drop. (The medical name for a slowed heart rate is bradycardia.) These breathing abnormalities may begin after 2 days of life and last for up to 2 to 3 months after the birth. Smaller and more premature infants are more likely to have AOP.

Although it's normal for all infants to have pauses in breathing and heart rates, those with AOP have drops in heart rate below 80 beats per minute. This causes them to become pale or bluish. They may also look limp and their breathing might be noisy. They'll either start breathing again by themselves or need help to do so.

AOP is different from periodic breathing, which is also common in premature newborns. Periodic breathing is a pause in breathing that lasts just a few seconds and is followed by several fast and shallow breaths. Periodic breathing doesn't cause a change in facial color (such as blueness around the mouth) or a drop in heart rate. Babies who have periodic breathing start regular breathing again on their own. While it can be scary to see, periodic breathing usually causes no other problems.

How Is Apnea of Prematurity Treated?

Most premature infants (especially those less than 34 weeks' gestation at birth) will get medical care for apnea of prematurity in the hospital's neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Right after they're born, many of these infants must get help breathing because their lungs are too immature to let them breathe on their own.

AOP can happen once a day or many times a day. Doctors will closely watch the baby to make sure the apnea isn't due to another condition, such as infection.

Medicines

Many babies with AOP get oral or intravenous (IV) caffeine medicine to stimulate their breathing. A low dose of caffeine helps keep them alert and breathing regularly.

Monitoring Breathing

Babies are watched continuously for any sign of apnea. The cardiorespiratory monitor (also known as an apnea and bradycardia, or A/B, monitor) also tracks the infant's heart rate. An alarm sounds if there's no breath for a set number of seconds, and a nurse will immediately check the baby for signs of distress.

If the baby doesn't begin to breathe again within 15 seconds, the nurse will rub the baby's back, arms, or legs to stimulate breathing. Most of the time, babies will begin breathing again on their own with this kind of stimulation.

A baby who still isn't breathing after being stimulated and is pale or bluish might get oxygen through a handheld bag and mask. The nurse or doctor will place the mask over the infant's face and use the bag to slowly pump a few breaths into the lungs. Usually only a few breaths are needed before the baby begins to breathe again on their own.

If Your Baby Is on a Home Apnea Monitor

Although apnea spells usually end by the time most preemies go home, a few will continue to have them. In these cases, if the doctor thinks it's needed, the baby will be discharged from the NICU with an apnea monitor.

An apnea monitor has two main parts:

- a belt with sensory wires that the baby wears around the chest

- a monitoring unit with an alarm

The sensors measure the baby's chest movement and breathing rate and the monitor continuously records these rates.

Before your baby leaves the hospital, the NICU staff will review the monitor with you and give you detailed instructions on how and when to use it, and how to respond to an alarm. Parents and caregivers also will be trained in infant CPR, even though it's unlikely they'll ever have to use it.

If your baby isn't breathing or their face seems pale or bluish, follow the instructions from the NICU staff. Usually, your response will involve some gentle stimulation, like stroking your baby's back, arms, or legs. If it doesn't work, start CPR and call 911. Remember, never shake your baby to wake them.

The doctor will let you know how long your baby should wear the monitor. Be sure to speak up if you have questions or concerns.

How Can I Help My Baby?

Apnea of prematurity usually ends on its own with time. Healthy infants who have had AOP usually do not go on to have more health or developmental problems than other babies. AOP does not cause brain damage, and a healthy baby who is apnea-free for a week will probably never have it again.

Aside from AOP, other problems with your premature baby may limit the time and interaction that you can have with your little one. But you can still bond with your baby in the NICU. Talk to the NICU staff about what would be best for your baby, whether it's holding, feeding, caressing, or just speaking softly. The NICU staff is not only trained to care for premature babies, but also to reassure and support their parents.

If your baby comes home with a monitor, it can be a stressful time. Some parents find themselves constantly watching the monitor, afraid to take a break even to shower. This usually gets easier with time. If you're feeling this way, the NICU staff can reassure you and perhaps put you in touch with other parents of preemies who went through the same thing.

© 1995- The Nemours Foundation. KidsHealth® is a registered trademark of The Nemours Foundation. All rights reserved.

Images sourced by The Nemours Foundation and Getty Images.