Atrial Septal Defect (ASD)

What Is an Atrial Septal Defect?

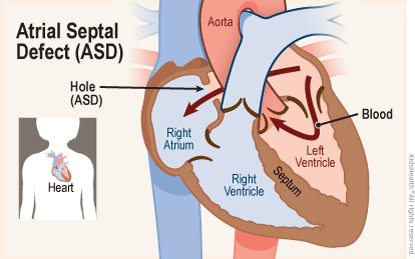

An atrial septal defect (ASD) — sometimes called a hole in the heart — is a type of congenital heart defect in which there is an abnormal opening in the dividing wall between the upper filling chambers of the heart (the atria).

In most cases, ASDs are diagnosed and treated successfully with few or no complications.

-

30-Second Summary: Atrial Septal Defect

Learn the basics in 30 seconds.

What Happens in an Atrial Septal Defect?

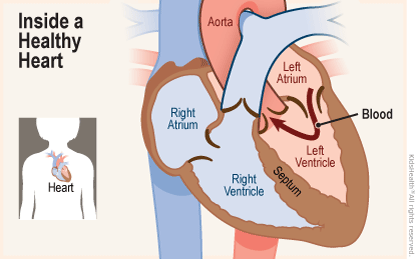

In an atrial septal defect, there's an opening in the wall (septum) between the atria. As a result, some oxygenated blood from the left atrium flows through the hole in the septum into the right atrium, where it mixes with oxygen-poor blood and increases the total amount of blood that flows toward the lungs.

The increased blood flow to the lungs creates a swishing sound, known as a heart murmur. The murmur, along with other specific heart sounds, often is the first tip-off to a doctor that a child has an ASD. ASDs can be in different places on the atrial septum and can vary in size.

What Causes Atrial Septal Defects?

Children with ASDs are born with the defect. ASDs happen during fetal development of the heart. The heart develops from a large tube, dividing into sections that will eventually become its walls and chambers. If there's a problem during this process, a hole can form in the wall that divides the left atrium from the right.

In some cases, the tendency to develop an ASD might be inherited (genetic). Genetic syndromes can cause extra or missing pieces of chromosomes that can be associated with ASD. Most ASDs, though, have no clear cause. It's also not clear why ASDs are more common in girls than in boys.

What Are the Signs & Symptoms of an Atrial Septal Defect?

The symptoms caused by an ASD depend on its size and its location. Most kids who have ASDs seem healthy and appear to have no symptoms. Most grow and gain weight normally.

Children with larger, more severe ASDs, though, might have some of these signs or symptoms:

- poor appetite

- poor growth

- extreme tiredness

- shortness of breath

- lung problems and infections, such as pneumonia

What Problems Can Happen?

An ASD that isn't treated in childhood can lead to health problems later, including an abnormal heart rhythm (an atrial arrhythmia) and problems in how well the heart pumps blood.

As kids with ASDs get older, they also might be at an increased risk for stroke because a blood clot could form, pass through the hole in the septum, and travel to the brain. Pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in the lungs) also may develop over time in older patients with larger untreated ASDs.

Because of these possible complications, doctors usually recommend closing ASDs early in childhood.

How Are Atrial Septal Defects Diagnosed?

After hearing the heart murmur that suggests a hole in the atrial septum, a doctor may refer a child to a pediatric cardiologist, a doctor who specializes in diagnosing and treating heart disease in kids and teens.

The cardiologist might order one or more of these tests:

- chest X-ray: an image of the heart and surrounding organs

- electrocardiogram (EKG): a record of the heart's electrical activity

- echocardiogram (echo): a picture of the heart and the blood flow through its chambers. This is often the primary tool used to diagnose an ASD.

How Are Atrial Septal Defects Treated?

Treatment of an ASD will depend on a child's age and the size, location, and severity of the defect.

Very small ASDs might not need any treatment. In other cases, the cardiologist may recommend follow-up visits for observation.

Usually, though, if an ASD hasn't closed on its own by the time a child starts school, the cardiologist will recommend fixing the hole, either with cardiac catheterization or heart surgery.

Cardiac Catheterization

Many ASDs can be treated with cardiac catheterization. In this procedure, a thin, flexible tube (a catheter) is inserted into a blood vessel in the leg that leads to the heart. The cardiologist guides the tube into the heart to make measurements of blood flow, pressure, and oxygen levels in the heart chambers. A special implant is positioned into the hole and is designed to flatten against the septum on both sides to close and permanently seal the ASD.

In the beginning, the natural pressure in the heart holds the device in place. Over time, the normal tissue of the heart grows over the implant and covers it entirely. This nonsurgical technique leaves no chest scar, has a shorter recovery time than heart surgery, and usually needs just an overnight stay in the hospital.

There's a small risk of blood clots forming on the closure device while new tissue heals over it, so kids who had a catheterization take a low dose of aspirin for 6 months after the procedure. Over time, the normal tissue of the heart grows over the device and the aspirin is no longer necessary.

After catheterization, a child should take it easy for a few days and might need to skip gym class or sports practice for a week or two.

Heart Surgery

Sometimes, when the ASD is very large or too close to the wall of the heart, a device cannot be safely used and heart surgery is needed to close the defect.

If your child has surgery, he or she will get general anesthesia and won't feel pain or be able move around during the surgery. The surgeon will make a cut in the chest, then stitch the hole in the atrial septum closed or sew a patch of manmade surgical material (such as Gore-Tex) over it. Eventually, the tissue of the heart heals over the patch or stitches, making the area smooth and nearly normal in appearance.

Kids usually can leave the hospital 3 to 4 days after surgery, if there are no problems. The first few days at home, your child should relax in bed or on the couch doing quiet activities such as reading, sleeping, and watching TV. Your doctor will let you know when your child can go back to school.

It takes about 6 weeks for a chest incision to heal. If there are no other problems and the cardiologist say it's OK, your child should be fully recovered and able to return to normal activities.

Heart surgery does leave a permanent scar on the chest. It will be sore at first, so the doctor might prescribe a pain reliever, or recommend acetaminophen or ibuprofen. Your child might feel numbness, itchiness, tightness, or burning around the cut.

For 6 months following catheterization or surgical closure of an ASD, antibiotics are recommended before routine dental work or surgical procedures to prevent infective endocarditis (an infection of the inner surface of the heart). When the heart tissue has healed over the closed ASD, most patients no longer need to worry about the risk of infective endocarditis.

Your doctor will discuss other possible risks and complications with you before the procedure.

After their ASD is closed and they've had plenty of time to heal, most kids have no further symptoms or problems.

What Else Should I Know?

In the weeks after surgery or cardiac catheterization, the cardiologist will check on your child's progress. Your child might have another echocardiogram to make sure that the heart defect has closed completely.

Most kids recover from treatment quickly, and will just need regular follow-up visits with their cardiologist. You might even notice that within a few weeks, your child is eating more and is more active than before surgery.

However, some signs and symptoms might indicate a problem. If your child is having trouble breathing, call the doctor or go to the emergency department immediately. Also call the doctor if your child has any of these symptoms:

- a bluish color around the mouth or on the lips and tongue

- poor appetite or difficulty feeding

- failure to gain weight or weight loss

- listlessness or decreased activity level

- a lasting or unexplained fever

- increasing pain, tenderness, or pus oozing from the incision

Having your child diagnosed with a heart condition can be scary. But the good news is that your pediatric cardiologist will be very familiar with ASDs and how best to manage the condition. Most kids who've had an ASD corrected go on to live healthy, active lives.

The care team is there to support you and your child. Be sure to ask when you have questions.

You also can find more information and support online at The American Heart Association.